June 13, 2006

June 13, 2006We went to town to buy ice cream. The summer evening was stifling hot and we cooled down after dinner by driving in my grandfather’s car with the windows rolled down. Then we cruised back out highway 109 to “the cabin”, as my grandfather called his small house in the country, at about twelve miles an hour. Dad-dad and Bonnie Cox sat in the front seat of their white 1960 Rambler American and I rode in the back eating an ice cream cone with a warm, twelve mile per hour breeze in my face from the two front windows. I was ten.

We pulled up behind another car, old and rusted, driven by a young couple. She sat close beside him and he wrapped his arm around her shoulder. They were doing maybe eleven. Life passes at a slower pace in rural Kentucky.

After a while, we reached a brief straight section of road and my grandfather pulled into the left lane to pass. As we sped by, my grandmother stuck her head out the window and yelled, “Get a room if you want to do that!”

My grandfather laughed. So, did I.

“Aw, Mother,” he teased, “You shouldn’t have said that. You’ll embarrass them!”

“Oh, they just smiled and waved.” she replied. Then she smiled, clearly proud of her misbehavior.

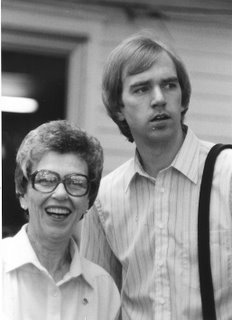

My grandmother died last week. I flew to the funeral in western Kentucky where she lived all her life and where I was raised. I expected much wailing and slow, grimacing, head shaking like I experienced at my grandfather’s funeral in the same place six years earlier, but for reasons I still don’t completely understand, there was precious little of that. It was surprisingly upbeat.

She may have been my grandmother, but in terms of parenting she was a second mom. My grandparents always lived close by and I remember spending almost as much time with them as I did my parents when I was little. After my father was killed in a car accident when I was twelve, my mother, two younger sisters and two younger brothers moved in with my grandparents. My mother enrolled in college and my grandparents pretty much raised my siblings and me for those four years.

To the rest of our family, the woman some of us grandchildren called “Bonnie Cox” was our matriarch. My aunt felt that calling her “Bonnie Cox” was disrespectful, and rightly so, so she became “Meemee” to my cousins.

As the oldest grandchild, I suppose I am to blame for calling her by her formal name. I don’t know how that began. I was told that I did it to avoid confusion with my younger sister, Bonny. Kids come up with unusual nicknames for grandparents, but any way you look at it “Bonnie Cox” is a strange nickname for a grandparent, even one named Bonnie Cox.

As we left the young couple in our proverbial dust, Dad-dad held a cigarette between the first two fingers of his left hand, occasionally flicking ashes out the open window as he steered with his right hand, which also held his milk shake. Occasionally, he would hold the wheel and the cigarette with his left hand while he took a sip from the cup with his right. The near total absence of traffic on 109 and our twelve-mile per hour top speed made this maneuver less dangerous than one might at first assume.

Directly, as he liked to say, meaning “not long thereafter”, he interrupted the silence with a serious thought.

“Bonnie?” he reflected.

“What, Bradley?”

“You know, when you’re driving down the road trying to steer the car with a cigarette in one hand and a milkshake in the other?” He spoke the next part slowly for emphasis. “Your ass will itch every time.”

The three of us howled.

My grandmother was funny, happy, likable and loveable. Maybe that’s a reason her services were more a celebration of her life than a funeral. For many years, Bonnie and Bradley lived in that small cabin with aluminum siding that he built on Niles Row Road, then a dirt and gravel road a few miles north of Dawson Springs off state highway 109. Before reaching Niles Row Road, 109 quickly passes Dunn Cemetery and then winds a couple of miles farther past another cabin my grandfather built long ago. The cabin on 109, built of logs and still inhabited, is where my mother was born. Dunn Cemetery is where both of my maternal grandparents now rest.

They had a concrete block foundation laid for the Niles Row Road cabin and then took me to see it. My grandfather lifted me onto the top of the block walls and I walked the perimeter while he told me what the finished cabin would look like.

“The living room and dining area will run all across the front of the house with a fireplace in the middle of the front wall,” he pointed out. The foundation wall formed a small rectangle, a little narrower than it was deep, and a smaller box jutted out of the front wall to support the planned fireplace.

“The bedroom will be on the back left side and Bonnie’s kitchen will be on the right. She says she doesn’t need a big kitchen. She wants everything to be handy.”

I had to stop when I reached the gap in the foundation wall where the door to the crawl space would eventually be and he helped me down. They lived in the cabin for a while with just a plank sub floor and in the winter cold air would filter up through half-inch gaps between the boards. After a few years, they had hardwood floors installed. The exterior was black tar paper for a long time, but was eventually covered with aluminum siding, white on the top half and red on the bottom. They lived most of their years in nicer, larger houses, but they loved that cabin and would occasionally move back to it “for a spell”.

They spent a lot of time over the years, as did I, cruising 109 to and from Dawson Springs. There were deer crossing signs on that stretch of two-lane blacktop that my grandmother must have passed a million times and ignored for the most part, until one summer evening’s after-dinner drive.

“Bradley?”

“What, Honey?” he asked.

“How do the deer know to cross here?”

We lauged at the inanity of the question, but she wasn’t offended. She laughed hardest. Being able to laugh at one’s self is a skill I wish she had taught me.

I also wish she had taught me to bake pies as well as she could. Though she gave me her recipes and countless pointers, no one could bake like my grandmother. Her chess and pecan pies were unbelievable. My father-in-law, Burton, whose wife Lidabel I believe to be the finest cook who ever approached a southern stove, says that no one could bake a biscuit like Bonnie Cox.

When my grandmother was in high school she had a male friend who had a truck and a job delivering something or other around the countryside. My grandfather’s parents had moved from their farm into town so he could go to school. That was unusual for his generation and he would eventually become not only the first in our family to go to college, but also the first to obtain a masters degree.

One day she asked her friend if he ever delivered in Charleston and if he knew Bradley Cox.

“Yes,” he said, “I see Bradley sometimes.”

“Next time you see him,” she instructed, “tell him that I wouldn’t mind going out on a date with him sometime.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

Bonnie Cox was always concerned with her appearance. She worked at staying thin, always had her hair done, and always wore attractive clothes. I remember her most often in shorts, sometimes slacks, because she was too active and worked too hard for dresses and skirts, but they were always nice looking outfits. The mortuary did an amazing job with her. She looked thirty years younger.

“If she were here right now,” I told my sister, “she’d say, ‘Damn, I look good, don’t I!’”

“She looks fantastic,” her daughter-in-law, Judy added. “The only part of her that doesn’t look perfectly natural is right around her mouth.”

“That’s because it’s closed,” her son, Tom chuckled.

Actually, it’s Tom and I have reputations in our family for never, ever shutting up. We have that in common with Bonnie Cox. And telling jokes. Our family laughs a lot, even at funerals. I think that's a good thing.

There were a lot of hard-working people in my family when I was growing up, miners, teachers, farmers, coaches, sawmill workers, but I got my work ethic from my grandmother. She worked every day in a factory sewing the same damn stitches over and over, a pocket for a pair of trousers or an inseam, perhaps, and I never once heard her complain. She would brag that she made “production” nearly every day, meaning that she had completed enough pieces to get paid a bit more. The factories were never air-conditioned and they were stifling in the summer. Still, she went to work every weekday looking nice and feeling happy.

One of the factories was nearly two miles from our home when I was in high school. My grandfather picked her up at work after he left the school where he taught political science and history and I attended, but occasionally he couldn’t for some reason or other or the car was in the shop and she would walk home. I had a friend near the factory so a few times in the summer I would play tennis with him and then walk home with my grandmother. She would work all day in a factory, walk two miles, cook supper for six of us and then wash the dishes. And she never complained. I never knew anyone who worked harder.

If I were asked to describe what it was like in my home during my high school years in a single scene, it would have to be around the dinner table. My grandfather would sit at one end of the table and I at the other, with my brothers and sisters on either side. One evening, I had finished eating and was about to push my chair back from the table when Bonnie Cox asked if I’d like some dessert. Given her baking prowess, this was not a question one dismissed lightly.

“Sure,” I said. “What do we have?”

“Well, what would you like?” she proposed.

“I’d like some cake.”

“Well, we don’t have any cake.”

“Well, what do we have?”

“Well, what would you like?”

“How about some ice cream?”

“I think we’re out of ice cream,” she informed me.

“What do we have?” I tried again.

“Well, what would you like?”

At this point, my grandfather, who was sitting at the opposite end of the dinner table and was not widely known as a patient man, laid down his fork and jumped in.

“Dammit, Bonnie! Will you just tell the boy what we have? He’s been guessing for half an hour now.”

In her eighties, Bonnie Cox’ driving skills diminished and she had a few minor accidents. Then a bigger one. Finally, the children decided they needed to intervene so they took her for a driving test. She failed and had her license taken away. Still, she insisted on owning a car and promised that a neighbor would drive her wherever she needed to go. She had a red car at the time and told them that she needed a white one that wouldn’t draw the attention of the police. This stipulation apparently went unnoticed by her children.

A few weeks later, of course, they learned that she had driven herself to Madisonville, thirty miles away, to do some shopping and they went to her home to confront her. She told them that there was nothing to worry about. “I got up early,” she explained. “I drove the back roads, got my shopping done, and was back home before the cops even got up.”

Bonnie Cox had a long history of skirting the motor vehicle laws of Kentucky. She taught me to drive when I was fourteen, which was nice except that the legal driving age was sixteen. By the time I got a learner’s permit and could legally sit behind the wheel, I had been driving for two years and could already drive better than the state policeman who administered my driving test. In fact, she taught several of the grandchildren to drive, all long before legal driving age. She was a great driving teacher, low keyed, unflappable. We learned in large parking lots before we went out on the road. The only rule was that Bradley couldn’t know. Nor, presumably, could his insurance company.

Once, my underage cousin Mark asked Bonnie Cox to take him somewhere after dinner. Bradley grabbed his keys and offered to drive him right then. Mark explained that it would be much better if his grandmother drove him and that he didn’t mind waiting. When the two of them returned an hour later, my grandfather was sitting in a chair reading. He lowered the newspaper and said, “Well, Mark, how does she drive?”

We could never be sure how much he really knew.

Both of my grandparents quit smoking at the same time about twenty years ago. At least that’s what he thought. He’d tell us that they hadn’t smoked for years and we’d smile and nod approvingly, knowing well that she smoked in their small bathroom by opening the window and rolling up a towel to seal the crack under the door.

After he retired, she wanted to buy some new dishes, but didn’t want to ask his approval so she waited each day until he took a nap. As soon as he dozed off, she walked to town and bought a dish. By the end of summer she had the full set. Their marriage wasn’t perfect, but it was good enough and they made it work.

After my grandfather retired, Bonnie Cox volunteered to help at the local nursing home. I’m not certain what she did there, but I believe she helped them sew and knit for recreation. She spent the last three years of her life living in that same home.

I visited her there as often as I could, but living six hundred miles away I could only manage a couple of visits or so a year. At first she was completely lucid, but her mental capacity slowly declined until our conversations would include stories from when she was my grandmother and stories from when she and I were in high school together. We would talk for hours and leaving her was one of the hardest things I ever did. I told myself that she wouldn’t miss me long because she wouldn’t remember that I had been there. That was probably true but it never really made feel any better about leaving.

One night last week, the nursing home called to say that her time was near. My mother and Tom rushed down to find her unconscious and, not knowing whether she would wake up, my mother sat next to her and spoke quietly near her ear, sharing feelings that she hoped her mother could somehow hear. Mom told me that she had been doing this for nearly a half hour when Bonnie Cox opened her eyes, looked at her daughter and very deliberately said in her best maternal voice, “Shut up!”

Then she told her daughter that it was past her bedtime. Apparently, she thought my mother was a teenager and was keeping her awake with all the talking.

My grandmother was born in 1914 and lived nearly 92 years. That means that she not only rocked, but at various times she was cool, neat, groovy, hip and the bee’s knees. Bonnie Cox always kept up with the latest thing.

We finished dinner and I went to my bedroom one Sunday evening when I was twelve. Bonnie and Bradley had come to our house in Madisonville to visit. It was February 9, 1964, a little after 8 pm CDT, to be exact. She came back to my bedroom to hurry me into the living room.

“Dirk, aren’t you going to watch the Ed Sullivan Show? Don’t you want to watch the Beatles?” she asked.

“What are the beagles?”

My dog, Lady, was a beagle and I thought she was pretty cool, so we started walking toward the living room’s enormous black-and-white TV set.

“The Beatles,” she corrected. “They have long hair and they sing really loud. They’re from England and they’re really the latest thing. Haven’t you heard about them from the kids at school?”

From the next room I heard, “She loves you and you know that can’t be bad. . .”. I had missed All My Loving and Till There Was You, but had made it in time for She Loves You, I Saw Her Standing There, and I Want To Hold Your Hand. My life was never the same. I suspect that makes me one of a handful of people from my generation who can say that his grandmother turned him on to the Beatles.

I’m glad my grandmother is no longer living in a nursing home. Maybe that’s another reason we were upbeat. During the funeral, I kept imagining her walking around in a pair of knee-length shorts looking like she did when I was in high school, free from her frail body and weakening mind.

She was married at age fifteen, gave birth to my mother in a log cabin when she was sixteen, was married to her childhood sweetheart for seventy years, had eight grandchildren, twenty-two great-grandchildren and four great-great-grandchildren, all who loved her dearly, lived to nearly 92 and was in good health for nearly all of it.

We should all be so blessed.