I eventually went to college, married and moved away to the city and, at a time and for reasons I can no longer recall, I began to drink unsweetened iced tea. I soon found sweetened tea cloying. I wouldn't drink a cola (colas, cokes, pop, soda and RC Cola being a related topic for another day) with spaghetti or a steak and to me sweetened tea is no different. Yes, I could once drink sweetened iced tea, but then I could once drink Boone Farm Apple Wine.

Now, don't get me wrong. I'm not making a value judgment about those who prefer their tea with sugar or honey or bourbon, for that matter, but having just returned to the South, I've noticed that it is an important social issue here and I find the entire matter intriguing, though I quickly admit this may be an indication that I have far too much time on my hands.

I love barbecue, the quality of southern barbecue having been one of the major drivers of my decision to return to the South, and sweetea seems to be a particularly touchy issue in barbecue joints. One very popular barbecue joint in our new town will only serve sweetea or soda. There are no unsweetened drinks on the menu. At another, the waitress reserves a special look of disdain for anyone who orders unsweetened tea. Then she pretends that she didn't hear your order. One refused to leave our table until I changed my mind. She just stood there looking at me, the queen of passive-aggression, until I said, "Make that sweetea, please".

A column in a local newspaper addressed this thorny issue last week and unequivocally posited that ordering unsweetened tea in a barbecue joint is just plain wrong (and in doing so, by the way, confirmed that I am not the only person here with too much free time). Furthermore, according to the author, ordering unsweetened tea isn't even grammatically correct in the South-- one should order unsweet tea.

I have seen "unsweet tea" on menus here, though rarely, and as best I can tell, this is not the correct use of the word. According to Princeton University's Wordnet, unsweet is an adjective meaning moderately dry, as in champagne, resulting from the decomposition of sugar in the fermentation process, or it can mean distasteful, as in "he found life to be unsweet". Unsweetened is the adjective that means not made sweet. So, I can have my tea sweet or distasteful?

Grammar police notwithstanding, I don't understand the logic behind having someone else sweeten my drink. What if I want to sweeten my tea with honey or an artificial sweetener? Too bad for me-- if you drink tea in a southern barbecue joint it will be sweetened and it will be sweetened with sugar. I've never known a restaurant or cafe to offer me sweetened coffee. They put sugar on the table and allow the customer to sweeten to their individual preference. Why, then, should they pre-sweeten my tea? Because it isn't simply a question of whether or not tea should be sweetened, but how sweet it should be.

My father-in-law insists on putting four spoonfuls of sugar in his glass of iced tea, which leaves about two spoonfuls undissolved in the bottom of his glass no matter how long he stirs. I tried to explain that cold water can only absorb so much sugar and beyond that point adding more sugar doesn't make the drink sweeter. He could heat the water and it would dissolve a bit more sugar, but then it would be syrup, or at best hot tea, and not iced tea at all. He explained to me that he sweetened his iced tea "to his taste" and, rightly, that it was none of my damned business. I wisely dropped the subject, but my mother-in-law continued to complain bitterly about the inch of wet sugar and lemon she had to clean from the bottom of his glass after every meal.

My oldest son, Cary, grew up in the Northern Virginia suburbs of Washington, DC, which is decidedly not southern despite its location below the Mason-Dixon Line. Now, twenty minutes drive outside of the suburbs and the landscape becomes seriously southern with more pickups than cars, gun racks, drawls and roadside bars, but that isn't where he grew up. In the Northern Virginia suburbs he knew more Asians, for example, than Bubbas and more lacrosse players than NASCAR fans. In the Yankee stronghold of the Washington metropolitan area, waiters don't even ask if you want sweetened or unsweetened tea. They serve iced tea and assume that if you want it sweetened, you'll add sugar.

Farther north, the situation is even more bizarre. I ordered iced tea in a Boston restaurant one autumn and was informed by the waitress that iced tea is a summer drink. I could order a cold beer in a snowstorm, a soda in a glass of ice, or even a milkshake, but there was apparently something about iced tea that made it undrinkable in the cooler seasons of New England. Maybe it was somehow tied to that revolutionary thing regarding tea and Boston Harbor, I don't know, but when she called the milkshake a frappe, I decided to just shut up and eat my lobsta'.

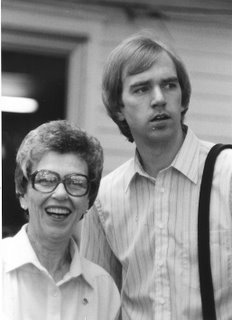

Since we recently moved to North Carolina, Cary has decided that he wants to out-southern his dad, even though I have a twenty-year headstart. He orders sweetea and shakes his head in disgust when I don't. He's an English major, though, and struggles mightily to justify unsweet as an adjective to describe tea. At least he's getting into the southern thing and I should be pleased that he isn't asking why the hell I moved him here. I should be happy that he considers my southern heritage worthy of emulation and, in fact, I am.

I suppose that, in the end, drinking sweetea is a requirement for membership in a club of which everyone who knows me already believes I was a founding member. I look, sound, think and act southern right up to the point when I say, "Unsweetened tea, please", the waitress drops her jaw and tray, and the other patrons give me that "he's an impostor!" glance.

Before my twenty-five years in Washington, I grew up hunting and fishing, riding in the bed of my grandpa's pickup truck, saying "yes ma'm", and knowing that the plural form of you is y'all, but I fear that my inability to reacquire a taste for sweetea may be the undoing of my re-initiation as a southerner.

And that would be unsweet.